Madeleine Vionnet, the Queen of the Bias Cut

Madeleine Vionnet was born in France in 1876. After leaving school, she began her seamstress apprenticeship at age 12. After a brief marriage at age 18 and the loss of a child, she left her husband to work in England. She eventually became a fitter for the noted dressmaker Kate Reily in London.

She returned to France in 1900 and worked as a toile maker at Callot-Soeurs. She later said of the sisters "without the example of the Callot-Soeurs, I would have continued to make Fords. It is because of them that I have been able to make Rolls Royces”. Her desire for simplicity put her at odds with the style of the house, which continued to be a problem when she then designed for Jacques Doucet between 1907 and 1911.

She founded her own house in 1912. It unfortunately had to close at the onset of WWI and did not reopen until 1919.

Between Vionnet, Chanel and Poiret, women were being liberated from their corsets and as such, active lifestyles became imperative to keep figures slim in the new fashions.

By 1923, she was employing 1,000 people. By 1925, she had a location on Fifth Avenue in New York.

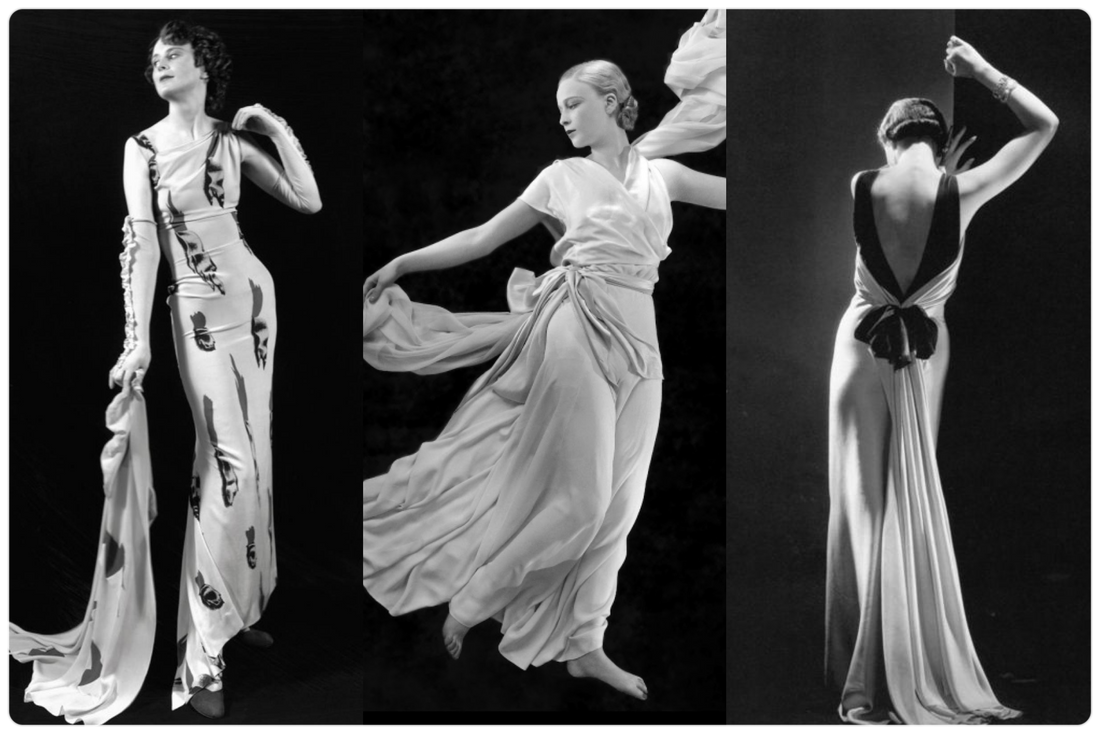

Her bias-cut clothing dominated fashion throughout the 1930s. Influenced by the modern dances of Isadora Duncan, Vionnet created designs that showed off a woman's natural shape. Like Duncan, Vionnet was inspired by Ancient Greek Art, in which garments appear to float freely around the body rather than distort or mold its shape.

Her gowns were worn by actresses such as Marlene Dietrich and Katharine Hepburn. Her vision of the female form revolutionized clothing. Vionnet used materials such as crêpe de chine, gabardine, and satin to make her clothes. Characteristic elements included handkerchief hems, cowl necklines and halter tops.

She instituted revolutionary labour practises such as paid holidays, maternity leave, day care, a subsidized dining hall and resident doctors and dentists.

Her campaign against the copyists began in 1921 with the creation of The Association for the Defence of Fine and Applied Arts. She photographed every creation from the front, back and sides, naming and numbering it, signing it and marking it with a fingerprint. Other couturiers followed her lead, but the battle for copyright laws in fashion were hard fought.

The onset of WWII forced her to close for the second time and she decided to retire, as business was already waning. As a result, she was somewhat forgotten for a time until, in 1977, Diana Vreeland created an exhibition of French fashion from between the wars under the title, "The 10s, 20s, 30s” which changed attitudes towards early 20th century fashion and towards Vionnet especially, who emerged as a true original of her time.

She is now considered one of the most influential fashion designers of the 20th century. She passed away in 1975 at the age of 99.

Elsa Schiaparelli

Elsa Schiaparelli was one of the most prominent figures in European fashion in the 1930s. She was a surrealist designer and collaborated with Salvador Dali and Jean Cocteau.

Her collections were famous for unconventional and artistic themes like the human body, insects, or trompe-l'œil, and for the use of bright colours like her "shocking pink".

She was born in Rome to an Aristocratic family in 1890. She was an imaginative, rebellious child and dreamed of escaping the trappings of her conservative parents and a life she considered unfulfilling. She fled to London to escape a marriage with a Russian suitor her parents favoured. There, she met the con-man Wilhelm Frederick Wendt de Kerlor and they married shortly thereafter. They lived off of an allowance from Schiaparelli’s parents but had to leave England when Wilhelm was deported for practising fortune telling. They bounced around Europe before moving to America in 1916. They opened a paranormal consultation business in the hopes of gaining fame. He came under BOI (now FBI) surveillance for his work and also for harbouring pro-German allegiance during wartime. They moved to Boston and continued their activity there. After their daughter was born in 1920, Wilhelm immediately moved out, leaving Elsa alone with a newborn baby. They later divorced and he was mysteriously murdered in Mexico. She returned to New York where she became involved with the Dada and Surrealist art movements.

She moved back to France in 1922 and got an expensive apartment in Paris. She assisted Man Ray with his Dada magazine for a short while before opening a fashion business, encouraged by her friend, the designer Paul Poiret. She launched a collection of knitwear in 1927 featuring sweaters with Surrealist trompe l’oeil images, which appeared in Vogue magazine. Her career really took off with a sweater that gave the impression of a scarf wrapped around the wearer’s neck. The collection expanded and she went from strength to strength.

She was one of the first designers to develop the wrap dress. She also developed the divided skirt, the first evening dress with a matching jacket as well as the Speakeasy dress during American Prohibition. She is credited with offering the first clothes with visible zippers, which became a key part of her designs and is renowned for her use of unusual buttons and innovative textiles.

The designs she produced in collaboration with Salvador Dali are among her best known, particularly the Lobster Dress (1937), famously worn by Wallis Simpson.

Her 98-room salon and work studios occupied the distinguished Hôtel de Fontpertuis.

When Paris fell during WW2, she moved again to New York where she remained for the duration of the war. On her return to Paris, she found that fashions had changed and she struggled to regain her footing.

She designed the wardrobe for several films including for Zsa Zsa Gabor’s role in 1952’s Moulin Rouge.

She eventually closed her business in 1954.

She set up another company in 1957 for her perfumes. It is this company that was later bought and is still running today.

Schiaparelli lived out the rest of her life comfortably and died in 1973 at the age of 83.

The failure of her business after WWII meant that Schiaparelli's name is not as well remembered as that of her great rival Chanel. However, in her time, she was far more original than most of her contemporaries and widely celebrated for her genius.

Augusta Bernard

Augusta was born in Provence in 1886. She began her career as a dressmaker, copying couture designs in Biarritz.

She opened up a studio in Paris in 1922 and specialized in creating long simple gowns, often in pale/pastel colours and cut on the bias. She became very popular in the 1930s, known for her neoclassical evening dresses, helped in part by the Marquise de Paris winning the ‘most elegantly dressed’ award at St. Moritz, Switzerland wearing a silver lamé Bernard design in 1930.

Americans often travelled to Paris to shop with her.

Vogue chose one of her gowns as the most beautiful dress of the year in 1932.

Her dresses were immortalized by photographers Man Ray in 1933 and George Hoyningen-Huene in 1934.

The Great Depression caused great difficulty for her business and she shut her shop and retired at the end of 1934.

She died in 1946.

Maggy Rouff

Born Marguerite de Wagner in 1896, Maggy’s parents opened a branch of the Viennese couture house Drécoll in Paris in 1902. She went on to work there as a designer when she came of age.

In 1929, now married and known as Maggy Besançon de Wagner, she bought Drécoll from her parents and renamed it Maggy Rouff.

She was known for her understated sportswear and lingerie initially and later for bias-cut feminine evening wear with use of draping, ruffles and shirring. She also loved asymmetry and innovative shapes.

She opened a London branch in 1937.

Maggy headed the Association for the Protection of Artistic Industries, an important anti-piracy trade network founded by Madeleine Vionnet in 1922.

She has 12 costume designer film credits between the late 30s and early 60s and she also authored two books.

Her clients included British royalty, Great Garbo and Grace Kelly.

She retired n 1948 and her daughter Anne took over the business. It eventually closed in 1965, failing to attract younger customers.

She died in 1971.

Elizabeth Handley-Seymour

Madame Handley-Seymour (née Elizabeth Fielding, born in Blackpool, 1867) was a skilled dressmaker who opened her atelier in 1908/9 at 47 New Bond Street, London. She began her career by copying the designs of Parisian couturiers, a common practise at the time. Some sources claim she had licensing agreements with Paul Poiret and the Callot Soeurs. She was assisted in her work by Avis Ford, who eventually became chief designer and fitter of the business.

Handley-Seymour created the costumes for the premiere of George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion in 1914, which were acclaimed by the fashion press. Of particular note was a dress based off a Poiret design which Shaw declared as ‘horrible’ and ‘dramatically nonsensical’.

During the 1920s and 30s, her gowns were in high demand by high-ranking socialites. It was Elizabeth Handley-Seymour who designed the wedding dress for the Duchess of York (later Queen Elizabeth & the Queen Mother) in 1923. The ivory chiffon moire dress was embroidered with pearls and silver thread, with a train of Flanders lace, and a girdle of silver leaves and green tulle fastened with silver roses and thistles.

She also made Elisabeth's coronation dress in 1937. It was made of English silk in a Princess shape with a full train. The dress was richly embroidered in gold, with gold beads, sequins and diamanté in a design repeating the floral emblems of the United Kingdom, Canada, New Zealand and Australia. Norman Hartnell designed the dresses for the royal maids of honour. Hartnell soon replaced Handley-Seymour as the go-to royal couturier.

When she started her career in 1908, she had a staff of four. When she retired in 1938, the staff totalled 200.

Queen Mary requested that Avis Ford open her own establishment after Elizabeth’s retirement. She agreed and continued to provide clothing to the Royal family.

Madame Handley-Seymour passed away in 1948.

In 1958 Handley-Seymours' daughter Joyce donated a number of her mother's design books ranging from 1910 to early 1940 to the Victoria and Albert Museum. The breadth and scope of the collection of 51 volumes of designs is seen as an unrivalled record of a court-dressmaker's work.

Valentina

Valentina Nicholaevna Sanina Schlee was born in Kyiv (in modern day Ukraine) in 1899. She was studying drama when the Bolshevik Revolution broke out and she fled the country. She married Russian financier George Schlee and lived with him in Athens, Rome and Paris. While in Paris, Valentyna performed with the dance troupes Chauve Souris and Revue Russe, which shaped her vision of theatrical costumes and her own dramaturgy of style. The couple arrived to New York in 1923 and became prominent members of Café Society. She initially tried to become an actress but her accent prevented her from landing roles. Valentina stood out as she did not adopt the flapper girl look popular at the time, instead opting for floor-length dresses. She wore accessories such as triangular hats and snoods, and once came to the opera wearing a hat filled with dry ice that made it look like smoke was coming out of her head.

She opened a couture business on Madison Avenue in 1928, immediately gaining success through famous clients she had befriended.

She entered the costume design world when she designed for stage actress Judith Anderson in ‘Come of Age’ in 1933. The costumes were better received than the play! She went on to design costumes for many great actresses of the day including Gloria Swanson and Katharine Hepburn. She designed the costumes for The Philadelphia Story on broadway in 1939.

A minimum price of $250 dollars was charged per dress in the 1930s. During this decade, she added elements inspired by European art and decorated dresses with Indian embroidery on the sleeves.

She also dressed the major socialites of the day including the Whitney and Vanderbilt women. Valentyna and George were a socialite couple themselves, and the press covered their lives in articles.

Her gowns were graceful and simple. She said in the late 40s that "Women of chic are wearing now dresses they bought from me in 1936. Fit the century, forget the year." Valentina’s sophisticated colour sense, influenced by Léon Bakst, gravitated toward subtle earth tones, “off-colours,” monochromatic schemes, and the ubiquitous black.

In the 40s, she softened the broad-shouldered silhouette popular in those years, presented short dresses and created ballet flats that people wore with stockings.

Fashion editors were exasperated by Valentina’s insistence upon selecting and modelling her clothes herself, but, ultimately, Valentina was right. Her business remained successful for 30 years. Vogue wrote in an article that only two designers, Valentina and Mainbocher, made couture in America in those years.

She earned mentions in the International best dressed list throughout the 40s and 50s.

She released her own perfume in 1950 called ‘My Own’. Around this time she began using variations of deep colours of damask and brocade. An average price for a dress was $600 dollars in the mid-1950s.

She closed her house in the 1957.

Her husband became known for an affair with Greta Garbo, who was a close friend and an avid customer of Valentina’s. In 1964, George died and left all his money to Garbo, though she did not attend his funeral. The two women lived in the same apartment building and it was reported that they actively avoided running into each other by setting up an elaborate schedule! In other reports it seems Valentina tried to remain friends with Greta.

She died from Parkinson’s disease in 1989.

In 2009, Valentina: American Couture and the Cult of Celebrity, a large retrospective exhibition, opened at the Museum of the City of New York.